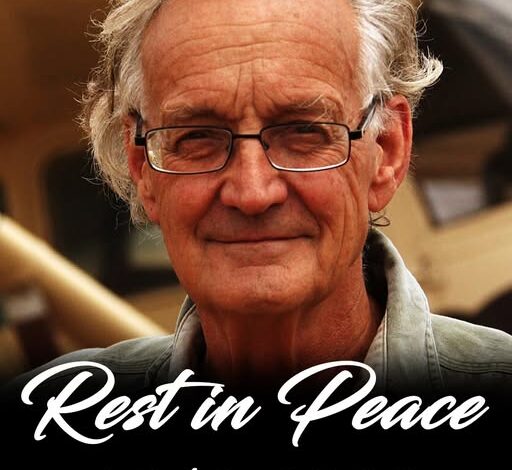

The world often pauses to mourn actors, musicians, and political leaders, but far less frequently do we stop to honor the people who quietly reshape humanity’s relationship with the natural world. This week, that silence felt heavier than usual. The global conservation community is mourning the loss of Iain Douglas-Hamilton, a man whose life’s work did not seek fame, yet permanently altered how humans understand, protect, and coexist with elephants.

Douglas-Hamilton passed away at the age of 83 at his home in Nairobi, leaving behind not only a grieving family, but an irreplaceable void in wildlife conservation, environmental science, and global biodiversity advocacy. To call him a zoologist would be an understatement. He was a pioneer, a whistleblower, a field scientist, and above all, a translator between worlds—human and elephant.

Before Douglas-Hamilton, elephants were often seen as symbols or spectacles. After him, they were recognized as thinking, feeling, grieving beings with memory, intelligence, and complex social structures. His research forced governments, conservationists, and the general public to confront an uncomfortable truth: humans were not just threatening elephants—we were misunderstanding them.

Tributes poured in from across the globe. Prince William described him as “a man who dedicated his life to conservation and whose work leaves a lasting impact on our understanding of elephants,” adding that his memories of time spent with Douglas-Hamilton in Africa would remain with him forever. Conservation leaders echoed the sentiment, with Charles Mayhew calling him “a true conservation legend whose legacy will endure long after his passing.”

Born in 1942 into an aristocratic family in Dorset, England, Douglas-Hamilton’s early life could have followed a comfortable, predictable path. Instead, he chose one defined by dust, danger, and deep immersion in the wild. After studying biology and zoology in Scotland and at Oxford, he moved to Tanzania in his early twenties, settling near Lake Manyara National Park. What began as academic research soon became a lifelong mission.

At Lake Manyara, Douglas-Hamilton did something revolutionary for its time: he treated elephants as individuals. He learned to recognize them by the subtle differences in their ears, tusks, scars, and personalities. He tracked family bonds, leadership hierarchies, mourning rituals, and long-term decision-making. “Nobody had lived with wildlife in Africa and looked at them as individuals yet,” he once said. That insight became the cornerstone of modern elephant behavioral science.

But alongside this intimate understanding came a horrifying realization. While documenting elephant lives, Douglas-Hamilton was also documenting their deaths. Poaching was not an isolated crime—it was an industrial-scale slaughter. Through dangerous aerial surveys, he revealed the true scale of the ivory trade’s devastation. Entire herds were vanishing. Landscapes once alive with movement were falling silent.

His work was not without risk. He was charged by elephants, nearly killed by swarms of bees, and even shot at by armed poachers while conducting research. Yet he persisted, compiling irrefutable data that shocked governments and international organizations into action. His findings were instrumental in securing the 1989 global ban on the international ivory trade, a turning point in wildlife protection history. He later referred to the crisis bluntly as “an elephant holocaust.”

Renowned primatologist Jane Goodall, who appeared alongside him in the 2024 documentary A Life Among Elephants, said Douglas-Hamilton helped the world understand that elephants “are capable of feeling just like humans.” That shift—from viewing elephants as resources to recognizing them as sentient beings—remains one of his most profound contributions.

In 1993, Douglas-Hamilton founded Save the Elephants, now one of the most influential wildlife conservation organizations in the world. Long before GPS tracking became standard, he pioneered its use on elephants, revealing migration routes spanning hundreds of kilometers and demonstrating how elephants make strategic decisions based on memory, environmental cues, and human pressure.

Frank Pope, CEO of Save the Elephants and Douglas-Hamilton’s son-in-law, said that Iain changed the future “not just for elephants, but for huge numbers of people across the globe,” emphasizing his courage, intellectual rigor, and moral clarity. Under Douglas-Hamilton’s guidance, conservation stopped being reactive and became data-driven, strategic, and globally coordinated.

His influence reached the highest levels of power. Collaborations with global leaders, including Barack Obama and Xi Jinping, helped pave the way for the 2015 U.S.–China agreements that dramatically restricted ivory markets, dealing a historic blow to illegal wildlife trade networks.

Across a career spanning more than six decades, Douglas-Hamilton received dozens of international honors, including the Indianapolis Prize, the Order of the British Empire, and appointment as a Commander of the British Empire. Yet those who knew him say accolades never motivated him. His true obsession was coexistence.

“I think my greatest hope for the future is that there will be an ethic developed of human-elephant coexistence,” he once said. It was not a romantic ideal, but a practical necessity. He understood that conservation would fail unless it accounted for the needs of both wildlife and the people living alongside it.

Douglas-Hamilton is survived by his wife Oria, daughters Saba and Dudu, and six grandchildren. But his legacy stretches far beyond family. It moves across Africa in the form of protected migration corridors, reduced poaching rates, informed policy decisions, and thousands of elephants whose survival can be directly traced to his work.

His ultimate dream, he said, was “for human beings to come into balance with their environment, to stop destroying nature.” In a world increasingly defined by environmental collapse and climate anxiety, that dream feels both urgent and unfinished.

Thanks to Iain Douglas-Hamilton, humanity is closer to understanding what that balance looks like. And because of him, the elephants still walk.