My name is Genevieve St. Clair, and at sixty‑eight, my life was a quiet testament to a mother’s enduring love. I lived in a small, paid‑off home in the heart of rural South Carolina—a place where the air was thick with the scent of jasmine and the evenings were filled with the gentle chorus of crickets. It was a simple life, a peaceful one. I knew which neighbor’s hound would start the midnight barking, which Tuesday the church ladies put out the lemon bars, and which grocery clerk would slip an extra coupon into my bag when the line got long. Peace accumulates like that—inch by inch, kindness by kindness.

But my heart, for the most part, lived six hundred miles away in a lavish new‑construction home in an exclusive suburb of Charlotte, North Carolina. That was where my daughter—my only child—Candace, lived with her husband, Preston Monroe.

I had spent my life as a nurse—a career of quiet service and profound sacrifice. I could start IVs in the dark. I could listen to a monitor and tell you, without looking, which patient was about to fall off a cliff. I had held hands that turned cold. I had whispered goodbyes strangers needed to hear. And every spare penny, every ounce of my best hours, had been poured into giving Candace the life I never had. She was my world, my legacy. The beautiful, ambitious girl destined for a horizon wider than our county line.

Years ago, when she and Preston decided to buy their dream house—a sprawling six‑bedroom monument to suburban success with a driveway that could host a parade—their ambition far outpaced their bank account. They couldn’t qualify for the massive mortgage on their own. I remember the phone call, the way a mother catalogs the weather on days that change everything.

Candace’s voice trembled with a practiced daughterly sweetness.

“Mama, it’s the perfect house. The perfect neighborhood. It’s the kind of place our children deserve to grow up in. But the bank—” she drew a breath that caught on her pride—”they said we need a co‑signer. Someone with more assets. More stability.”

I did not hesitate. What is a lifetime of sacrifice for if not to be summoned, one final time, on the day your child says please?

I drove the long hours to Charlotte, to a cold, impersonal bank office that smelled like carpet glue and fear, and I put my entire life on the line for her. I co‑signed the mortgage—a number so large it set my palms sweating through the pen. And more than that, for the past three years, I had been secretly paying a significant portion of their monthly note from my own modest pension—a quiet infusion of cash to keep them afloat. It wasn’t charity, I told myself; it was continuity. The soft hands under a tightrope.

What begins as mercy calcifies into expectation. Over time, Candace came to treat the deposit as weather—reliable, unacknowledged, background. The beautiful house, the catered weekends, the European‑tile bathrooms became, in her mind, evidence of personal triumph. My name receded to a line on a contract she never reread. My love became plumbing: essential and invisible until it stopped.

We spoke in postcards and polite emojis. I saw her life through the glass of a phone—golden light, long stems of wine, white kitchen countertops with lemons in perfect bowls. I told myself that distance is normal, that children grow busy. I told myself a thousand soft lies a mother keeps in a pocket for when the wind turns cold.

Then came the news that filled me with a clear, ringing joy: Candace was pregnant. My first grandchild. A new heartbeat entering a family that had been only two for too long. The baby shower would be grand—catered, curated, the sort of event sponsors mistake for marketing collateral. I was not invited—no embossed envelope found my mailbox—but the uninvited are how family surprises are made. I knitted a white blanket with a scallop edge, every stitch a prayer I couldn’t speak out loud.

On a bright Saturday, I wrapped the blanket in tissue, tucked a card inside—”For you, little one. Love, Grandma”—and started the engine of my old sedan. Gospel hymns rose from the radio, tinny and brave. The odometer clicked its quiet arithmetic. Pines gave way to interstates, truck stops to toll booths, and I drove a long ribbon of hope north until the exit signs began to pronounce the names that lived in my daughter’s voice.

Driving gives you time to remember. I saw Candace at sixteen, ink on her fingers, charcoal moons on her wrists. She wanted a summer at an arts program in New York. The tuition steamrolled my budget; the dorm deposit ate the crumbs. So I stacked night shift on night shift until dawn looked like a rumor. I walked rooms that smelled of alcohol swabs and grief. I clipped pulse oxes to fingers that clutched at nothing. I learned that love and exhaustion can sit at the same table and never once argue. When the acceptance letter came, I tucked a check beneath it and watched my daughter’s face light like a stage. There is no drug, no hymn, no sunrise that feels like that look on a child’s face when you open a door they thought was locked.

I arrived in their neighborhood as laughter began to spill onto lawns. The Monroes’ house stood with the confident squareness of new money—two stories of brick, a porch that announced itself, lanterns like polished commas. Cars lined both sides of the street like a dealership had tipped over. I parked near a honey locust tree and walked slowly, smoothing my dress, rehearsing the first moment—her surprise, her hands to her mouth, the laugh we would share when she said, “Mama, you shouldn’t have!”

The front door was open. Cool air spilled onto the porch. Inside, the rooms were dazzling—white roses in glass towers, balloons grazing a ceiling so high voices sounded brighter beneath it. A quartet in the corner coaxed something elegant from a playlist. Women in gauzy blue drank champagne from coupes. Men in shirts the color of lake water diced jokes into small, expensive laughter. The cake was a sculpture; the gifts, an unwrapped catalog.

I stood just inside the threshold like a tourist who accidentally stepped into a gala tour. Then I saw her—the orbit point of the room. Candace glowed in a pale dress that made her look both queenly and fragile. One hand under her belly, one on the stem of a glass. Her smile was perfect. Her eyes, when they found mine, were not.

Her expression collapsed in on itself, order to alarm in a single breath. She crossed the room quickly, friendliness shedding from her like confetti on a wet shoe. Her fingers found my elbow with a pressure I recognized from years of guiding patients back to bed.

“Mama,” she hissed, steering me onto the porch. “What are you doing here? You can’t be here.”

I looked at her, at the face I had once kissed for fever every hour on the hour. “I drove up to surprise you. For the baby.”

She laughed once—flat, airless. “A surprise? This is a catastrophe.” Her eyes flicked over me the way a hostess appraises a stained tablecloth. “Your dress. Your hair. You don’t fit in here. Preston’s parents are inside. What will they think?”

A sentence can bruise. I glanced down at my clean, Sunday dress, at the shoes that had done honest miles, at the gift bag cradling the blanket. Shame rose in me like heat off asphalt. The party thrummed an inch away; we were two planets on the porch where the air felt suddenly thin.

Preston appeared in the doorway, expensive anger buzzing under his jaw. He didn’t address me; he never had. He spoke to his wife as though a waiter had delivered the wrong course.

“Candace. Handle this. Now.”

She did. Her face arranged itself into something composed and cold. “You have to leave, Mama. You’re ruining my party. You are ruining everything.”

She turned her chin slightly. A man in a dark suit—silent, capable—stepped forward from the foyer. Security is the word people use when they have already decided who is safe to humiliate.

“Ma’am,” he said, not unkindly. “I’m going to have to ask you to come with me.”

I did not argue. There are losses that unmake the mouth. He walked me down the long, manicured driveway while guests paused mid‑story to watch. I felt their curiosity the way you feel rain before it falls—static along the scalp. A woman in chiffon whispered, “Oh my God, is that her mother?” I kept my back straight. The blanket rustled in its tissue like a small animal that knows it will not be kept.

I sat in my car for an hour. Maybe more. Time, when it breaks, sifts. The laughter gathered and thinned and gathered again. Somewhere, a flute of champagne tipped and glass argued with tile. My hands lay quiet in my lap. No hymn came to mind. The blanket lay on the passenger seat, unoffended by rejection, which is the mercy of things that cannot remember.

Humiliation has a taste—metal and lemon, bright and bitter. But under it, something colder moved. A line tightened inside me, the line that had held IV poles at 3 a.m. and arguments in school offices and a house together when the roof wanted to surrender. My love had been mistaken for weakness. My sacrifice, for servitude. I had been made a liability. I remembered the paper I had signed and the position my name occupied upon it. Bedrock.

I drove home through the night. Headlights scraped the road into pieces and put them back together. Fury is a poor navigator, but clarity sits in the passenger seat and reads the map without trembling. By dawn, my house on its quiet street breathed me in like it always did. Inside, I went to the metal file cabinet that had kept funerals and warranties and the lease from my first apartment safe enough to grow cobwebs. I found the mortgage—their mortgage—the sheaf of paper thick as my wrist, words dense as a winter forest.

I read. Slowly at first, then with the steady appetite of a woman who discovers that the story she is holding is about her, after all. There it was, where the lawyer’s finger had tapped all those years ago: covenants and conditions. The language didn’t shout; it never does. It simply allowed. If the primary co‑signer formally notified the bank of an irreparable breakdown with the borrowers—if her willingness to guarantee evaporated beyond recovery—the bank reserved the right to reevaluate risk and, if necessary, call the loan due in full. A clause tucked into the mortar. A kill switch.

A smile found me. Not giddy. Not cruel. The satisfied curve of a lock sliding open because you finally remembered which way to turn the key.

I slept on Sunday. Small, purposeful sleep. I watered my hydrangeas. I mended a pillow. I set out my church dress and then put it back because quiet has its own liturgy. On Monday morning, I packed the folder into my purse and drove not to Charlotte, not to a confrontation that would only feed hunger I no longer felt, but to Columbia, South Carolina. A hotel with a lobby that smelled of lemon oil and air conditioning took me in and gave me a room where the curtains closed all the way.

At ten sharp, I called the number for the bank’s risk management department—the one that lives on a page you only find when you look like you mean it.

“Risk Management. This is Sarah.”

“Good morning, Sarah. My name is Genevieve St. Clair. I am calling to report a material change in circumstances regarding a mortgage on which I am the primary co‑signer.”

Keys clicked. Professional boredom tried to keep its footing. “Loan number?”

I gave it. Address. My Social Security number. Date of birth. A lifetime arranged into digits that proved I could pull this particular fire alarm.

“I have the account. What’s the nature of the change, Mrs. St. Clair?”

“I am formally withdrawing my financial and moral guarantee for this loan. There has been a sudden and severe breakdown in my relationship with the primary borrowers—my daughter and son‑in‑law. I can no longer, in good conscience, vouch for their character or their financial stability. I am officially reporting this loan as high risk of imminent default.”

The tone on the other end sharpened. Boredom stepped back from the edge. “That is a very serious statement. Can you provide details?”

“On Saturday,” I said, “I was escorted from the property by a hired security guard at my daughter’s request during her baby shower. My presence was deemed an embarrassment. This constitutes a severe breakdown in the family relationship as contemplated by the covenants. Additionally, I have reason to believe their financial picture is more precarious than represented at origination. I will not be a party to that risk.”

Silence. Not the kind that ignores you. The kind that listens for the sound of a hinge failing somewhere inside a machine.

“Thank you, Mrs. St. Clair,” Sarah said at last, voice leveled now, all edges put away. “We will escalate this to legal immediately. A senior loan officer will be in touch shortly.”

I hung up and let the quiet of the hotel room settle like new snow. I ordered soup and a salad and ate both without tasting either. I watched an old movie where people apologized when they should and kept their promises because the script required it. I slept, not as a mother, but as a witness who has finally handed her testimony to a clerk and been told to sit down.

The next morning, Mr. Davenport from Legal called. The voice of a man who keeps the wolves fed and the fences high. He asked me to repeat myself. I did. He asked whether my decision was final. It was.

“Thank you for your candor, Mrs. St. Clair,” he said. “We’ll review the agreement and take all necessary steps to protect the bank’s interests.”

We both understood the euphemism. Protecting interests meant uncoiling the full length of policy built precisely for moments when the bedrock walks away.

The letter went out by certified mail that Thursday to Mr. and Mrs. Monroe. It cited Clause 17B—the Material Adverse Change provision—and declared the full outstanding balance due within thirty days. It offered an alternative: refinance the entire loan without the original co‑signer, subject to standard income and credit verification. The bank does not gloat; it simply sets a table and invites arithmetic to eat.

Panic moves faster than mail, but they met each other on Candace’s porch. I did not see her read the letter. I can, however, imagine the progression—annoyance at the bureaucratic envelope, confusion at the first paragraph, the cold bloom of understanding when the phrase “due and payable in full” sat up straight on the page. I imagine she reached for her phone before she reached for her husband. That’s the order of operations in a house like that.

When she called, I was folding laundry in the hotel room, a habit the hands remember even when the head has gone very quiet.

“Mama!” Her voice was raw. “The bank sent a letter. They’re calling the loan due. They said—” she tripped on the words—”they said you withdrew your support. What did you do? You’ve ruined us!”

I let the air carry her panic to the window and back.

“I told the truth,” I said. “That the relationship you and I had is irreparably broken. You announced it on your porch with a security guard. I simply repeated it to the people who funded the house built on my name.”

“That was a misunderstanding,” she said, old tactics reaching for new ground. “We were under pressure. Preston’s parents—”

“You made a choice,” I said gently, the way I used to tell patients a result they already knew. “Choices have consequences. Without my tacky, country name on your mortgage, your fancy life is less secure than you thought.”

“We’ll be homeless,” she said, the word turned suddenly holy in her mouth.

“That does sound like a problem. Perhaps speak to your husband. He seems to have solutions for appearances. See if he has one for arithmetic.”

I ended the call. My hand did not shake. I sat with the hum of the air conditioner and understood something I had taught a thousand families in quieter forms: sometimes mercy arrives dressed as a boundary.

What followed was not a single dramatic collapse but a series of small, devastating surrenders that added up to ruin. Banks returned their refinance applications with polite versions of no. Underwriters prefer numbers to narratives; the numbers did not bend. Their incomes without my deposits were too thin. Their credit cards dragged like anchors. A lender I had never heard of offered a rate that would have turned the house into a yoke even a stronger pair than they could not pull. They declined, which is to say they delayed the inevitable.

The FOR SALE sign arrived like a verdict and rooted itself on the Monroes’ perfect lawn. Real estate photos brightened rooms that had once brightened them. The listing copy offered “motivated sellers” and “quick close” and “bring all offers,” which are the prayers people pray to Mammon when dignity is all that’s left to tithe.

Friends evaporated. People who had answered their invitations in under a minute now replied to texts with a silence that looked like Sunday. Preston learned how quickly a golf foursome reshuffles when a man stops ordering the second round. Candace learned the speed at which a woman’s name can be un‑tagged from a charity board when rumors of foreclosure meet the ears of a treasurer who never liked her tone.

They fought. I did not need to be there to hear it; anger has an architecture you can sketch from memory. Blame echoes differently in a house gone half‑empty. You can tell where a marriage is by how they say each other’s names when the dishwasher breaks. Their arguments ricocheted through rooms designed for parties and not for truth.

They called me again. Begged. Bargained. Offered apologies with the ink still wet on their self‑interest. “Just call the bank and tell them it was a mistake,” Candace pleaded one night, voice thin and hoarse. “Co‑sign again. Please. We’ll lose everything.”

“I wish you the best,” I said. And meant it. Then I blocked the number, not as punishment, but as a cast around a broken limb that needs stillness to remember how to be a bone.

The house sold at a loss. Closing day arrived unannounced for them the way winter arrives in the South—from the edges inward. They moved smaller. Boxes marked with black marker. A couch that looked different in the light of a rental. Their marriage, built on a scaffolding of show, groaned when the banners came down. In time, it folded. People said they were surprised. People always are when a beautiful façade retires from its position and reveals the scaffolding was never meant to be load‑bearing.

I went home. I planted fall greens. I replaced the chain on my porch swing. Neighbors asked after my daughter and I said she was finding her way. In the afternoons, I sometimes took the white blanket out of its tissue and ran my fingers along the scallops. I did not cry. Grief is not always a river; sometimes it is a stone you learn to hold without asking it to be anything else.

Weeks later, an envelope arrived with no return address. Inside was a note on heavy paper, the corners of which were bent as if reconsidered many times. The handwriting was Candace’s, and also not.

“Mama, I don’t know who I am without the house. I don’t know how to be without the people who liked me when I had it. I’m sorry for the porch. I’m sorry for the guard. I’m sorry that I forgot who paid for the horizon I pretended I had earned. I am angry at you. I am angry at me. I am pregnant and tired. If you don’t want to see me, I deserve that. If you do, I will come to you. I will wear what you tell me and bring whatever dish the church ladies need for Wednesday. Love, Candace.”

I read it twice, then set it by the breadbox. Some reconciliations need heat; some need time. I made tea. I sat with the silence and let it decide nothing. Boundaries are not doors that never open; they are doors with locks that finally work.

The baby was born on a Tuesday in late October, under a sky so sharp and blue it felt like you could slice your thumb on it. I did not hear from them that day. I baked two loaves of cinnamon bread and left one on the porch of a neighbor whose husband had gone for a checkup and come back with a different word. I walked to the mailbox and found it empty and felt both relief and disappointment. That is the weather of motherhood—sun and shadow on the same square of lawn.

Two weeks later, another envelope. A photo this time. A small face, eyes closed, mouth open like a surprised O. The blanket—my blanket—wrapped tight, the scallops visible around the edges like a soft white crown. On the back, in Preston’s tidy block letters: “Thank you.”

I set the photo on my kitchen shelf between the salt and the pepper. I resumed my life. I was not waiting. Waiting is a posture that injures the back. I simply kept the house ready in the way women do—guest towels laundered, cobwebs evicted, a jar of hard candy that reminded me of every nurse’s station I had ever worked.

One Sunday afternoon, there came a knock. I knew that knock the way you know the first note of a hymn. I opened the door. Candace stood there in jeans and a sweater a little too thin. Her hair was pulled back without ceremony. The baby slept in a car seat at her feet. No entourage. No choreography. Just my daughter and her child and the space they had made by losing a house.

She looked at me the way people look at water when they’ve been thirsty long enough to stop pretending they are not.

“Mama,” she said.

I stepped back and opened the door wider. I did not gather speeches. I did not calculate debts. I pointed to the table. “There’s soup,” I said. “And cornbread if you’re hungry.”

She laughed and cried at the same time, the way babies do before we teach them to separate their emotions into rooms. She carried the car seat in and set it on the chair by the window where the sun warms first. We stood side by side and looked at the little face together. Her hand found my sleeve, not to pull me elsewhere this time, but to hold on where she stood.

We did not fix everything that day. We ate. We burped a baby. We napped the kind of nap that forgives. Later, when the sky bruised into evening, she asked if she could stay the night. I made up the guest bed and left the door open. In the cradle of ordinary, people remember who they are.

I tell you this not because revenge isn’t satisfying—it is. The boundaries I drew saved me, and perhaps saved her, too. The bank did what banks do. The house became someone else’s, as houses do. But dignity, once reclaimed, is not an act; it is a home you carry. A woman can be escorted from a porch and still keep the deed to her name.

They called security on me. I called the bank on them. Both calls did exactly what they were designed to do. And still—when my grandchild yawned in that white blanket, I learned the old lesson for the thousandth time: love is not the opposite of consequence. Love is what allows consequence to do its work without turning either party to stone.

I live now the way I have always wanted to live—quiet mornings, jasmine evenings, church on a Wednesday, soup on the stove. Sometimes I take the long road into town and count the miles the way I once counted shifts. Six hundred is a big number until you measure it against the distance between pride and humility. That distance is the longest drive a person will ever make. I am glad I made it home.

In the weeks after I said I was glad to be home, life folded back into its ordinary rhythms the way a sheet folds to a sharp corner—simple, practiced, precise. I changed the filter on the air‑conditioner. I scrubbed the sink until it flashed a small constellation back at me. I mended the elbow of the cardigan I wore on night shifts when the hospital was colder than it had any right to be. I did not check my phone for updates about the Monroes. The news knew how to find me if it needed to.

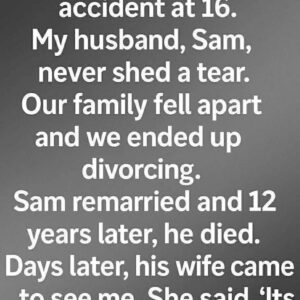

It did, in drifts. Not gossip—topsoil. A nurse I used to precept now worked in Charlotte and texted, without malice, that she’d seen Preston in the urgent care with blood pressure so high it put numbers to his pride. A woman from my church, whose sister’s neighbor’s cousin did staging for real estate, reported that the Monroes had moved the crib into the living room for the listing photos because the nursery looked cramped on camera. I let each drift settle. Then I swept my porch and watched wrens make their fast opinions along the fence.

One afternoon, while I was shelling butter beans into a blue bowl, Mr. Davenport called again. I recognized the number and almost let it ring into the garden. But there is courage in answering.

“Mrs. St. Clair, good afternoon. I wanted to inform you of next steps. The borrowers have inquired about forbearance. We’ve declined. They’ve also initiated a refinance application with three lenders. All have requested verification of your continued support. Given your notice, that verification will not be provided.”

He paused, the way men do when they’re about to say something that drops a stitch in the conversation. “They may pursue a short sale. If so, we’ll cooperate. Our objective is to be made whole.”

“I understand,” I said. “Thank you for calling me directly.”

“You were the bedrock of the file, Mrs. St. Clair,” he said, voice softening an inch. “When the bedrock moves, our maps change.”

After we hung up, I took the ledger book from the drawer by the stove. For three years, I had written a line on the first of each month: Monroe mortgage support, then the amount, and a small check mark beside it the way a schoolgirl would grade her own homework. I ran my finger down those check marks and felt the warmth I had felt every time the deposit went through—that private glow of having turned money into future. The warmth was honest. It had been love. The mistake had been in believing love must always be indistinguishable from subsidy.

I made a pot of chicken soup and brought it to Miss Alma two doors down, whose ankle swelled in July and refused to return to its normal life. We ate on her porch and watched boys on bicycles argue about the best way to skid. “You look lighter,” she said, squinting at me in the late sun.

“I am,” I said, surprised by the truth of it. “I finally put down a sack I’d convinced myself was my spine.”

At night I dreamt less about rooms I wasn’t welcome in and more about the house I had built for myself out of objects that knew my hands. Thread, wooden spoon, hymnal. In the morning, I walked the long edge of town and counted the barns. A hawk watched me from a pine as if my steps might flush something it could use.

Meanwhile, in Charlotte, a good realtor did what good realtors do. She took photographs that made corners look wide and windows look friendly. She brought in a woman who could make a bowl of apples look like a life decision. She advised Candace to hide the brand‑name totes and the aggressive bottles of juice cleanse—buyers prefer to believe a house is sleek but eats biscuits in private. She fixed the asking price at a number that let the Monroes keep a straight face while letting the market bring them to their knees.

On the first open house Sunday, Preston wore a blazer that fit like a dare, and Candace wore a dress that told the story of a woman unbothered by the arithmetic taped to the inside of her skull. Neighbors milled. Lookers looked. Couples whispered in the primary suite with the kind of conspiratorial lust that makes mortgages breed. The realtor, with her perfect hair and better posture, invited people to picture Christmas. To picture sunlight at 10 a.m. in March. To picture themselves belonging to a zip code.

And still—the offers came in thin and low. One contingent on the sale of another house that would itself take a miracle. One from an investor who sent men in boots to knock on baseboards and then deducted the sound from the price. One earnest young couple who wrote a letter about their toddler and their dog and the way the backyard would let them invent a childhood out of scraped knees and sprinklers; their number was sweet and impossible.

Candace started waking at 3 a.m. with a panic that felt like it had a heartbeat of its own. Preston began to pace. His mother called to inform Candace, in the tone of a woman announcing a new wallpaper selection, that “this is why class matters—people will forgive anything if they like your last name.” Candace hung up and cried on the kitchen floor with her head next to the kick plate, which reflected a stranger with red eyes and mascara like rain.

I did not know these details then. I would learn some later; I would deduce others. But even without the particulars, I knew the shape of the days. Pride does not go quietly—it knocks over lamps on its way out.

On a Tuesday heavy with heat, I received a letter from the bank confirming that the loan had been referred to the special assets team. Jargon loves dignity. The translation was plain: the wolves had the file now. Along with the letter, a brochure on counseling services for guarantors caught in family financial disputes—a small mercy stapled to a large machine. I put the brochure in a drawer. I was not in dispute. I had already decided.

Time passed. The hydrangeas browned at the edges, and the church ladies debated whether to switch to poinsettias early to save money. I canned peaches for the first time in a decade and burned one thumb and laughed out loud alone in my kitchen because of it. The body remembers joy even when the head has misfiled the paperwork.

Then the sale happened. Not the sale they’d wanted—no triumph, no champagne sabers in the driveway. A clean offer from a family who did not care about the school where the Monroes had applied for a spot in line for a spot in the lottery for the privilege of saying their child might someday attend. This family wanted a house with a roof that did not ask questions of the sky. They wanted a mortgage they could pay without becoming a personality they hated. They closed. The bank breathed. A deficiency remained—a number that would trail the Monroes like a dog they didn’t feed. Arrangements were made.

The move was uncinematic. Boxes labeled with handwriting that got meaner as the day went on. A man in a rented truck who asked where the powder room was and forgot to shut the door on his way back, letting a rectangle of July pour into the foyer. The realtor left a bottle of cava on the counter with two plastic flutes and a card that said, “Onward” in thick gold ink. Candace put the bottle in a trash bag she termed donations and thought, for one clear minute, about walking out the front door without her phone, her rings, or her husband. She did not. She went upstairs and took the shower curtain down because it was hers.

Their new place was two bedrooms over a nail salon and a tax prep office. The first night, the baby hiccuped in utero so hard the mattress trembled and Candace laughed in surprise and terror. Preston slept like debt: shallow, frequent, loud.

I learned the address weeks later, printed on the back of an envelope that held the photo of my grandchild in my blanket. I stared at those numbers the way a pilgrim might study a map that stops two miles short of the shrine. I did not drive there. The urge came like a wave and left like one. I let it go.

I did drive to the hospital when her labor started—not the Charlotte one where she’d curated a birth plan that included a playlist and a lip balm, but the one near their new apartment where the L&D nurse wore a scrunchie and a sense of humor. I did not go inside. I parked across the street and timed my prayers to the length of red lights. When the lights changed, I watched men carry deli bags into the building and thought of all the babies who arrive into rooms where sandwiches share space with miracles.

A day later, the photo arrived. A week after that, another letter, shorter than the first.

“Mama, the stitches itch. The baby is perfect. I am tired in my bones. Preston does not know how to be useful and is trying to fix it with noise. I am trying to learn humility without becoming a doormat. Do you have a recipe for that? Love, C.”

I laughed and cried and wrote back with a recipe for soup and a story about the time I put a diaper on backward in the middle of a grocery store because sleep had called in sick. I did not give advice. Advice is a coin that loses value when passed hand to hand too quickly. I offered presence the way an old tree offers shade—no instructions, only a place to rest that does not ask your name at the gate.

Autumn stretched its careful nets across the fields. I took out the box of things from when Candace was small—report cards that praised her attention to detail and warned about her friendship with girls who loved mirrors; a program from the eighth‑grade play where she was the only child who remembered everyone else’s lines; the Polaroid of her first apartment key, held up like a medal. I thought of all the ways we raise children to be strong and all the ways we forget to teach them that strength is not the same as display.

One evening, with the light slanting into the kitchen at an angle that makes saucepans look holy, there came that knock I knew in my bones. We had our soup and our cornbread, our first nap and our second. When they settled into bed, I sat in my chair by the window and held my hands still on my knees. The house made the small sympathetic noises houses make when they understand the people inside them are trying. I slept without dreaming.

In the months that followed, we made a life that was not a movie and therefore had a better chance of lasting. On Tuesdays I drove up with a casserole and left on Wednesdays with a laundry basket that smelled like a person I had not met until the day I saw her wrapped in my blanket. Candace learned to budget in three colors. Preston learned to say, “I was wrong” without treating the words like a barbed wire fence. He found a second job that did not require explaining who he used to be.

There were relapses. The day the baby shower photos resurfaced on a friend’s social media with a caption that read, “What a perfect day!” Candace went cold as marble, then snapped at me over how I folded burp cloths. I almost answered with the sharpness I had honed to a fine edge in rooms where grief taught me to cut fast to save something living. Instead, I set the cloth down and said, “I’m going to make tea.” We drank our tea in silence, and when she said, “I’m sorry,” I believed she was apologizing to herself, too.

December brought its complicated geographies of joy and obligation. We agreed—gently, without combat—that I would not be in rooms where people still wore the performance of a last name like armor. We planned our own small Christmas, the three of us, in my kitchen with the good plates and the candle that smells like oranges if you pretend hard enough. I bought the baby a wooden rattle and the softest set of pajamas I could find that did not advertise anything.

On Christmas Eve, the baby fell asleep on my chest, weight like a cure. Candace washed dishes and hummed the tune of a carol we both knew and could not remember the words to. If grief had walked up my front steps then and knocked, it would have been embarrassed to find us so busy with peace.

One morning in January, my pastor preached about forgiveness and managed not to confuse it with memory loss. After service, Miss Alma took my hand and said, “I like the way you’re doing it. You’re not pretending the harm didn’t happen. You’re just refusing to let it get the last word.” I squeezed her fingers and said, “That’s because I finally learned the alphabet. Last words are for authors. I am only a witness.”

Sometime in spring, the bank sent me a final letter marked RESOLVED. The account was closed, the deficiency structured into payments that could be made without performance. The file number that had once felt like a policy over my head became paper I could use to level a crooked table. I lit a match over the sink and burned the carbon copy of my monthly ledger entries one by one, watching ash turn my careful check marks into a snow I did not have to shovel.

When the baby began to pull herself up on furniture and grin like she’d invented gravity, Candace asked if she could bring her to the church picnic. I said yes with the kind of yes a person earns by saying no when it counted. The women who had sent casseroles when my mother died cooed and told stories about colic as if it had been a small prank the universe used to play but gave up because we stopped laughing. The men took turns letting the baby gum their knuckles and claimed she had the grip of a fisherman. We ate fried chicken and potato salad and the kind of watermelon that turns bowls into red bells.

There were moments still—the kind you tuck under a magnolia leaf until the heat tames them. A day Preston’s mother came to town and called me by my first name in a voice that tasted like coins. I answered, “Mrs. St. Clair will do,” in the tone that makes dogs stop barking. Another day, Candace cried in my driveway because pride is a creature that sheds in clumps, and sometimes you find it on the rug after you thought you’d brushed it all away. We put the kettle on. We kept going.

On the first birthday, the baby smashed cake with both hands and then looked at her fingers like she’d discovered a way to hold joy. Candace took a photo and, without asking, printed a copy for my fridge. Later, when I took the trash out, I stood under the sky and said a word I don’t often say out loud. Thank you. Not to any audience that might applaud, not to any system that could claim credit. To the quiet fact of having come this far with the parts of ourselves we could carry and the parts we could no longer afford to.

You may want to know whether I ever regretted the call to the bank—whether I ever wished I’d swallowed the insult on the porch and given my daughter one more month, one more check, one more benefit of a doubt that had already been exhausted. I did not. Mercy without boundary becomes complicity. There is a version of this story where I soften the edges for comfort. I would not trust that story to hold anyone’s weight, least of all yours.

Sometimes, when I pass the honey locust tree where I parked that day, I think of the woman I was on that street—the gift bag on the seat, the radio trying its best, the heart leaning forward like a child at a window. I bless her for going. I bless her for leaving. I bless her for the drive home and for the call she made in a hotel room that smelled like lemon oil and new beginnings. And then I go buy stamps and birdseed and a small bouquet of grocery store flowers for my table, because ordinary is the throne where dignity sits when it is not busy rescuing you.

On the baby’s second spring, Candace and I walked the long edge of my town and counted the barns. “Three,” she said, lifting the little one higher on her hip. “Four,” I said. “Five,” the baby declared with the authority of the recently bipedal. We laughed. A hawk watched us again from the same pine. Or another hawk. Or the same kind of hawk. Some things change names. Some simply change angles and keep watching.

We reached the top of the rise where, on a clear day, you can see the church steeple and the water tower and the promise that if you keep walking, you can come back by a different road and still call it home. Candace turned to me and said, without ceremony, “Thank you for not saving me the way I asked you to.”

I took her hand. “You saved yourself the hard way. I only stopped making it harder.”

We stood there, three people who had once been one person and would someday be three entirely new ones, and let the wind have our hair for a minute. Then we went back down the hill to my kitchen, where soup was waiting, and the good plates, and a wooden rattle that had learned to keep time with a small, insistent life.

I drove six hundred miles for a smile that did not appear. I made a different smile happen instead, one that lives now on a fridge, on a porch, in a pew, at the top of a hill where a child counts barns out loud and gets the numbers wrong and is right anyway because the point is not the count. The point is the counting. The point is that we kept walking.